The Impact of Artificial Lighting on Nocturnal Wildlife

By the Site Ecology Team (SET) and Wildlife and Industry Together (WAIT)

April 20, 2015

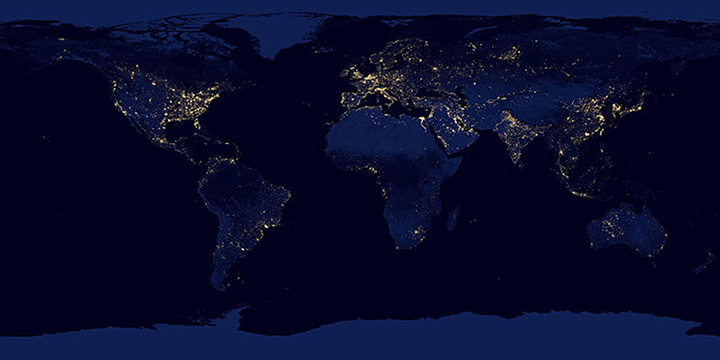

We rarely stop to think that the night is necessary and good for life. Therefore, we do not realize that protecting the night sky is a valuable step to conserving bio-diversity. Most people think that, as we sleep at night, the rest of the species do the same, with a few exceptions, so it is of no concern if we send out a little light into the night time environment …[IN REALITY]… the biological activity of our fauna is more intense at night than during the day and this fauna needs the night for their normal activities.

How can Light Pollution be defined so we understand what it is?

In an attempt to shed light on the effects of non-natural light in the environment during normal periods of darkness, multiple factors must be considered and evaluated. We recognize the need and often the requirement for safety and security reasons. We, as part of the ecosystem know the importance of a healthy environment and bear the responsibility of realizing that our own health and wellbeing is affected by modifications that are made.

According to the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), the term light pollution refers to “any adverse effect of artificial light, including sky glow, glare, light trespass, light clutter, decreased visibility at night, and energy waste.” The IDA further states that light pollution “wastes energy, affects astronomers and scientists, disrupts global wildlife and ecological balance, and has been linked to negative consequences in human health.”

We are diurnal, dependent on the sunlight to see, active during daylight with an ingrained fear of the dark. Since the discovery of fire, man has used the light from fires to see at night and to keep wild animals away. In addition to moonlight, this artificial light gave man a sense of safety and wellbeing. Light became part of the way of life.

With the invention of the electric light, the night sky was no longer filled with just natural light from the moon and stars.

Well why does it matter that there is artificial light at night? Who does it hurt? Walls' 1942 paper says that all species of bats, badgers and most smaller carnivores, most rodents (besides squirrels), 20% of primates, and 80% of marsupials are nocturnal, and many more are active both night and day.

Studies are beginning to illuminate possible problems with living in a world that doesn’t comply with nature’s photo-periods (i.e. duration of sunlight as determined by season (photoperiodic—internal clock governed by how long the day is).

This darkness interruption has dangerous and disruptive side effects for insects, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and humans. The effects extend to migration, navigation, plant blooming as well as when trees lose their leaves. All activities are affected by the period of light and not temperature. A season’s photoperiod is the only consistent factor in the natural environment. Therefore, many species of plants and animals rely on the length of the night to indicate the proper season for budding & flowering, mating, molting, and other life cycle activities. The timing between flowering and pollinators or gatherers may not mesh. This photoperiodic sensitivity is often so acute that many species can detect discrepancies in natural light as short as one minute. Reproductive cycles are most often disrupted when artificial light at night interferes with species’ natural detection systems.

Change in light signals the start of activities as foraging (feeding & substance), sheltering, mating and reproducing (fireflies & frogs), and communicating (glowworms & coyotes). Artificial lights alter an animal’s circadian rhythm and create miss-cues.

Lights can draw & disorient (hatchling turtles, night flying moths, frogs & amphibians, birds) or repel from the area thus forming barrier leading to habitat loss (rodents, many bats), especially site specific ones.

Photo courtesy of Luciof

Migrating birds of which there are 450 species that use moon and stars, can be attracted by light beams (high-rises, towers, light houses, oil platforms). Direct flight birds are less affected than circulating, curved path flight patterns.

Animals can be blinded (deer-in-headlights), leading to an increase in road kills. For nocturnal species that only use rod cells in their eyes to see, such a sudden change in illumination saturates their retinas rendering the animal instantly blind. Once they do venture into the dark areas, it will take 10 to 40 minutes before their rod cells can function as effectively as before and their night vision fully returns. Lighting can be very disorienting for animals that are trying to move at night. So wildlife corridors can be compromised by even a single light and so prevent animals from moving across the landscapes.

Predators have an advantage by seeing over a greater area, and their prey must seek darkness and spend more time hiding. Lighting changes the predator/prey relationship. The prey has less time to use for normal activities.

What is the biological affect? Melatonin production, which is dark dependent, is suppressed when the dark is interrupted at night. “Melatonin is involved in circadian rhythm regulation, sleep, hormonal expression of darkness, seasonal reproduction, retinal physiology, antioxidant free-radical scavenging, cardiovascular regulation, immune activity, cancer control, and lipid and glucose metabolism. It is also a new member of an expanding group of regulatory factors that control cell proliferation and loss and is the only known chronobiotic hormonal regulator of neoplastic cell growth”. [Source]. Artificial light is linked to diabetes, depression, failure at school, and difficulties in concentrating. Some studies indicate a link between artificial light and obesity as well.

On our campus, the NIH Office of Research Facilities has undertaken a long term re-lamping program to change out over 300 roadway and walkway lamps to lower energy LEDs and to redirect the light beams only where needed. The program, when completed, will insure that the Federal Security mandates for illuminating our campus are met. It will also help to:

- Reduce CO2 emissions: The same as removing 53 cars from the road a year

- Reduce waste: We will throw away 1,474 less bulbs over the next 20 years

- Eliminate mercury: The LEDs will eliminate any mercury entering the environment from our streetlights

The walkway lights that were installed comply with the IDA dark sky requirements (mentioned above). One benefit to the new LED fixtures is that each of the 120 LEDs that make up the fixture contains a different shaped lens that directs the light from that LED to a specific spot. This allows the fixture to perfectly match its rated lighting distribution pattern resulting in very little bleeding beyond the fixture’s rated cutoff. The LED roadway fixtures have zero up lighting unlike previous lighting technologies that relied on reflectance within the fixture itself to direct light to the ground. The individual LEDs only project light forward resulting in the use of all of the produced light. The roadway lights were designed with a light distribution pattern that spreads the length of the roadway. In addition, the lights are aimed at the roadway in an effort to provide a sharp cutoff so that adjacent areas are not illuminated.

How can we reduce light pollution and lessen the impact on our environment and the organisms that inhabit it?

Some Institutes and even cities have adopted a “Lights Out” program in which exterior lighting as well as interior lights in tall buildings are dimmed or turned off during periods of bird migration. Bare bulbs or upward pointing lights are replaced with hooded fixtures that only shine downward. If lights can’t be turned off, then use flat lens, and reduce the number of lights and intensity. Both the height of the pole and the intensity of the lamp should be adjusted to only direct light where needed.

Here are some actions you can take at home:

- Turn off lights not needed

- Use wavelengths that do not affect wildlife or attract insects (yellow)

- Keep lights away from wildlife habitat, especially endangered

- Be eco conscious

- Get educated

- Raise awareness by sharing knowledge

It should be realized that decisions have to be made between cost, safety, health, and environmental wellbeing. Whatever the result, our total inter-relationship with our environment must be considered.

We would like to thank William (Kyle) Hawkins, Mechanical Engineer, Facilities Management Branch, RTP, Division of Facilities Operations and Maintenance, Office of Research Facilities for his input.

References

- 10 Ways That Light Pollution Harms The World by Lance David LeClaire, Listverse, 14 August 2014.

- Effects of Artificial Night Lighting on Terrestrial Mammals - : Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting. Catherine Rich & Travis Longcore (eds). 2006. Island Press. Covelo, California. Pages 15-42.

- About Lighting Pollution - Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

- Light Pollution Taking Toll on Wildlife, Eco-Groups Say - Sharon Guynup, National Geographic Today, April 17, 2003

- The Effect Of Artificial Light On Birds And Wildlife - : Monique Cousineau, November 10, 2011

- Light Pollution Harms the Environment

- How Light Affects Human Melatonin Levels

- Light and human health: LED risks highlighted

- The Dark Side of LED Lightbulbs, September 15, 2012

- The vertebrate eye and its adaptive radiation, Walls, Gordon. L., Cranbrook Institute of Science, 1942)